Titanium machining rarely behaves the way newcomers expect. On paper, the metal looks ideal—high strength, low weight, and corrosion resistance that holds up where stainless steel fails. But once titanium meets a cutter, everything changes. Heat concentrates at the edge, tool pressure rises faster than anticipated, and even a well-planned toolpath can drift if the setup doesn’t stay perfectly stable.

Teams that work with titanium often learn quickly that the material doesn’t reward shortcuts. It responds to heat, rigidity, chip flow, and geometry in ways aluminum and stainless steel never will. Understanding how titanium behaves—both as a material and inside a CNC machine—is the difference between repeatable accuracy and expensive trial-and-error. This guide breaks down the real factors that shape titanium CNC machining and explains the engineering choices that bring consistency to Grade 2 and Grade 5 components.

What Makes Titanium a Preferred Material for High-Performance Machined Parts?

Mechanical and thermal advantages

Titanium enters the conversation whenever strength, weight, and long-term durability sit higher on the priority list than machining convenience. Its tensile strength approaches many steels, but its density sits far closer to aluminum. That combination shifts load paths, reduces mass in structural components, and allows complex parts to operate under higher stress without fatigue failures. Titanium also delivers chemical stability and corrosion resistance in environments where stainless and aluminum begin breaking down. For engineering teams designing parts that must survive heat cycles, saltwater, or biological exposure, titanium isn’t a premium alternative—it’s often the only material that offers predictable performance across decades of use.

Application-driven material performance

The properties that make titanium difficult to machine are the same ones that protect it during real-world use. Low thermal conductivity prevents heat transfer, which becomes useful in aerospace components that sit near engines or friction-heated surfaces. High stiffness and fatigue resistance play a direct role in airframes, landing hardware, and structural brackets. In medical environments, biocompatibility allows implants to stay stable inside the body for years without corrosion or reaction. Engineers lean on titanium when a failure would be unacceptable or when a design pushes mechanical limits that more common alloys cannot meet.

Common grades used in CNC machining

Most CNC-machined titanium falls into two categories: commercially pure Grade 2 and the widely used Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5). Grade 2 machines slightly easier because of its ductility and lower strength, making it suitable for corrosion-resistant hardware and low-stress components. Grade 5 dominates aerospace, medical, and high-performance industrial work because it holds rigidity and strength at elevated temperatures. Despite their differences, both grades behave similarly under a cutter: heat gathers quickly, shear forces stay high, and edge wear appears faster than in stainless or aluminum.

Why Do Many Shops Consider Titanium Difficult to Machine?

Heat concentration and thermal load

Titanium refuses to distribute heat. When the edge enters the cut, nearly all thermal energy stays at the tool–workpiece interface. On aluminum, heat travels into the chip; on stainless steel, it moves into the part; titanium sends it straight into the cutter. This concentrated heat softens coatings, oxidizes edges, and accelerates wear long before the program reaches its midpoint. Even when parameters are conservative, the metal Machining generates enough temperature to distort chip flow and push the tool toward premature failure.

High shear strength and cutting resistance

Titanium does not shear cleanly. The chip forms through force, not ease, and the tool absorbs that force with every pass. Where aluminum allows high-speed machining and stainless steel tolerates moderate aggressiveness, titanium pushes back. The result is sustained cutting pressure that amplifies tool deflection and raises cutting forces. Deep pockets or ribs amplify this effect, especially when long-reach end mills come into play. That combination—high heat, high load—explains why titanium machining requires a grounded strategy rather than speed.

Elastic recovery and tolerance shift

Titanium tends to rebound slightly after deformation, a behavior often overlooked until tolerances begin drifting. Thin walls bow during cutting and return to shape once the tool retracts. Bores contract after machining, especially when roughing generates temporary heat expansion. If the program doesn’t anticipate this springback, parts show unexpected thickness, taper, or a need for corrective passes. The effect exists in other metals, but titanium exaggerates it enough to influence how finishing passes are planned.

Work-hardening tendency

Localized heat buildup can harden sections of the surface mid-cut. When the tool re-enters that hardened region, wear accelerates rapidly. The surface may show faint color changes or inconsistent finish long before dimensional accuracy fails. Titanium’s ability to hold heat makes this work-hardening cycle more frequent and less forgiving. Stable chip load and sharp edges reduce the risk, but titanium always pushes the process toward thermal imbalance if the cut loses stability.

How Does Machining Titanium Actually Behave Inside a CNC Machine?

Chip formation and heat retention

Titanium chips exit the cut hotter than most machinists expect. Their color reveals the truth of the cut: pale chips indicate steady temperature; dark violet or blue chips point to heat spikes. Long, stringy chips show rubbing or poor chip evacuation, while short chips confirm proper engagement. Because titanium holds heat, even a well-tuned cut can reach temperatures that alter tool coatings. This is why chip behavior is often the first indicator of how the program is performing.

Tool deflection and stability challenges

Even with rigid setups, tool deflection becomes noticeable the moment cutting forces rise. Long tools bend subtly; pocket floors flatten unevenly; sidewalls show faint waviness. Titanium amplifies every small mechanical weakness in the system—toolholder rigidity, spindle bearings, fixturing, and even the order of operations. The material’s resistance to shear creates lateral force that works against the tool unless engagement is tightly controlled.

Thermal expansion impact on accuracy

Heat causes titanium to expand locally during roughing, which means a part can measure correctly while still warm but drift once it cools. Internal bores, thin ribs, and flatness readings reveal this cooling shift. When the cut is deep or the cycle long, parts must rest before inspection or the tolerance measurements will not reflect their true state. Titanium’s expansion isn’t extreme, but it is predictable—and ignoring it leads to subtle dimensional errors.

What Techniques Are Most Effective for Machining Titanium?

Tool geometry and coatings

Tools for titanium need sharp edges, rigid cores, and coatings built for heat resistance. TiAlN, AlTiN, and similar coatings outperform others because they maintain hardness at elevated temperatures and resist oxidation. A strong edge reduces rubbing, while proper flute geometry encourages chip evacuation. Tools designed specifically for titanium regularly outperform general-purpose carbide, especially in long cycle times.

Recommended speeds, feeds, and DOC

Titanium rarely accepts “fast and aggressive.” Stable surface speed and a feed rate that maintains chip load typically deliver better results than pushing for speed. Too little chip load causes rubbing and heat; too much generates overload and chatter. Once the sweet spot appears, cutting forces stabilize and tool life increases noticeably. Engineers treating titanium like aluminum or mild steel usually learn quickly that this metal demands moderation rather than speed.

Coolant flow and chip evacuation

High-pressure coolant keeps titanium machining stable. It flushes chips before they recut, removes heat from the edge, and improves tool life. When roughing deep pockets, the coolant’s ability to clear chips influences more than the toolpath itself. A stable coolant stream often prevents localized temperature spikes that lead to work hardening. Machines capable of 1,000 psi or more have a visible advantage when working with titanium.

Fixturing strategy for thin-wall sections

Titanium’s stiffness transfers vibration easily, so the fixturing must anchor the part without allowing flex. Thin sections benefit from machining sequences that preserve mass until the end. Temporary support ribs or adaptive roughing paths reduce stress. Fixture placement becomes a design consideration when engineering thin fins, deep channels, or tall ribs in Grade 5 titanium.

What Machining Methods Work Best for Titanium Components?

3-axis and 5-axis CNC suitability

Three-axis CNC handles basic geometries, but titanium’s cutting load makes 5-axis machining preferable for many parts. Shorter tool lengths, better access, and optimized approach angles reduce deflection and extend tool life. Components with angled pockets or multi-face features gain the most from 5-axis positioning.

EDM for deep or tight features

Titanium responds well to EDM because the process avoids cutting forces entirely. When features involve very deep slots, narrow channels, or internal corners a tool cannot reach, EDM removes material without adding stress. Many hybrid workflows combine CNC roughing with EDM finishing to maintain accuracy while reducing tool wear.

Hybrid machining setups

Some titanium designs benefit from switching between milling, turning, and EDM within a single生产 cycle. Roughing on a mill, precision finishing on a lathe, and EDM for inaccessible geometry keeps cost and accuracy aligned. Titanium doesn’t reward forcing a single technique—choosing the right combination provides measurable benefits.

What Tools Are Needed to Machine Titanium Reliably?

Tool materials and coatings

Carbide remains the standard for titanium, but the grade and coating determine performance. Heat-resistant alloys with reinforced edges last longer under sustained load. PVD coatings maintain hardness even when edge temperatures exceed several hundred degrees Celsius.

Toolholder rigidity

The entire structure—from spindle taper to collet to holder—must absorb pressure without movement. Shrink-fit or hydraulic holders often outperform standard ER collets in titanium because they eliminate micro-movement that contributes to chatter.

Coolant and lubrication requirements

High-pressure systems, through-spindle coolant, and proper nozzle alignment directly influence tool life. Without reliable coolant delivery, even the best tool geometry loses stability within minutes.

What Parameters Matter Most When Setting Up Titanium CNC Machining?

SFM, feed rate, and depth of cut

Titanium requires a balanced parameter set. Surface speed tends to remain lower than other metals, feed must stay consistent, and depth of cut must avoid thin, rubbing passes. Engineers often adjust only one variable at a time during setup to observe heat response or chip shape.

Engagement strategies

Constant tool engagement methods such as adaptive roughing prevent overload. Sudden tool engagement spikes cause heat bursts and edge chipping. Maintaining smooth, predictable engagement is far more important in titanium than in aluminum or mild steels.

CAM toolpath considerations

Toolpaths must minimize dwell and sudden direction change. Trochoidal paths, optimized entry angles, and constant-chip-load strategies reduce heat and preserve edge integrity. A poorly chosen toolpath can double the temperature at the tool edge even with correct parameters.

Where Are CNC-Machined Titanium Parts Commonly Used?

Aerospace structures

Titanium forms the backbone of high-temperature, high-fatigue aerospace components—airframe brackets, engine-adjacent structures, landing hardware, and pressure housings. Machining quality directly influences their flight-life consistency.

Medical implants and surgical instruments

Implants require clean surface finish and dimensional reliability. Surgical tools rely on titanium’s rigidity and corrosion resistance. CNC machining remains the most reliable method for producing patient-specific geometries and small batches.

Energy and industrial hardware

Chemical plants, marine hardware, and pressure systems rely on titanium for corrosion-proof structural function. Valves, pump components, and heat-exposed fixtures frequently specify titanium where stainless begins to degrade.

How Much Does Titanium CNC Machining Cost?

Factors influencing machining cost

Titanium increases cycle time, tool usage, and programming demands. The biggest cost drivers are part geometry, grade selection, tool wear, and machine time. Parts with deep cavities or weak stiffness require slower strategies that extend runtime.

Grade-to-grade cost differences

Grade 5 costs more to machine because the cutting resistance and heat generation exceed those of Grade 2. The extra strength improves performance in final use but demands tighter machining control.

Design impact on quoting

Thin walls, sharp internal corners, deep pockets, and narrow slots increase machining difficulty and cost. A minor radius increase or thickness adjustment can dramatically reduce machining time on titanium. If you’re unsure, sharing the model early often reveals your biggest cost levers.

What Tolerances Can Be Achieved When Machining Titanium?

Typical achievable tolerances

Most titanium work holds ±0.02 mm without difficulty when the setup is stable. Tighter tolerances remain possible but require strict heat management and minimal tool reach.

Thermal effects on precision

Heat expansion influences true dimension more than tool wear in many titanium jobs. Measuring immediately after machining often produces false readings because the part cools into its final shape minutes later.

Inspection and quality verification

CMMs, probing routines, and precision gauges ensure accuracy. Titanium parts settle reliably after cooling, making consistent inspection timing part of the process rather than an afterthought.

How Can Engineers Improve the Surface Finish on Titanium?

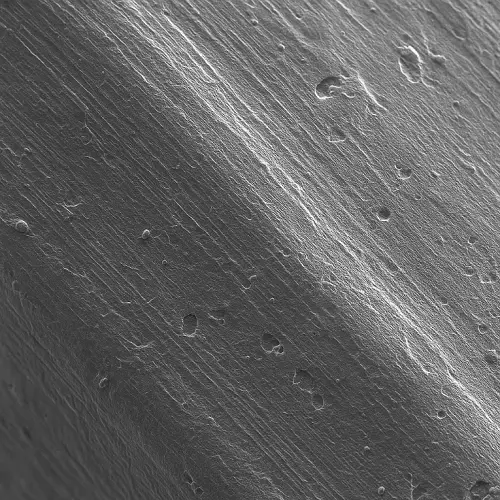

Causes of poor finish

Excessive heat, rubbing passes, and tool deflection all leave visible patterns on titanium surfaces. Even small vibrations can translate into surface waviness.

Stable finishing strategies

Light radial engagement, fresh edges, and controlled SFM produce the most stable finish. Removing only the minimal amount of material during finishing prevents thermal buildup.

Post-processing options

Bead blasting, polishing, and light surface treatments refine finish where machining alone isn’t enough. Some aerospace and medical components require additional finishing to optimize functionality.

What Design Tips Help Reduce the Difficulty of Machining Titanium?

Geometries that increase risk

Tall ribs, narrow slots, deep pockets, and ultra-thin walls stress the machining process. Titanium magnifies these challenges due to cutting resistance and heat retention.

Optimized thickness and radius choices

Adding radius at internal corners and maintaining consistent wall thickness reduces tool load. Even a small design change can lower cycle time significantly.

Sequencing and manufacturability improvements

Machining order determines stiffness. Preserving structural support until final passes prevents part distortion. A short DFM check often identifies opportunities to simplify machining.

What Advancements Are Changing Modern Titanium Machining?

New tool coatings

Advanced PVD coatings withstand higher temperatures and maintain sharper edges longer than older formulations. They directly influence cycle time and tool cost.

High-pressure coolant systems

Modern coolant systems push chip evacuation and temperature control beyond what older equipment could achieve. Machines equipped with 1,000–2,000 psi coolant consistently outperform low-pressure systems in titanium.

Modern CAM algorithms

Adaptive clearing, constant-engagement toolpaths, and real-time tool load monitoring changed titanium machining behaviors. CAM improvements alone can reduce temperature spikes and extend tool life dramatically.

When Should You Send Your Titanium CAD Model for Review?

Features that require early feedback

Thin walls, deep cavities, unsupported ribs, and heavy pockets all deserve early review. These features determine tool reach, vibrational stability, and heat behavior.

DFM insights on heat, stiffness, and tool reach

Sharing the CAD model early reveals manufacturability risks that directly influence cost. A simple modification—radiusing a corner, shifting wall thickness, or adjusting a pocket entry—often cuts hours off complex titanium jobs. If you’re working with titanium for the first time, early engineering feedback saves both time and iterations.

Upload Your Titanium CAD for a Review

Titanium rewards careful machining but reacts strongly to heat, stability, and design decisions. If your project involves Grade 5, thin pockets, or deep cavities, sharing the CAD early helps avoid avoidable machining time. JeekRapid can evaluate tool access, thermal behavior, and manufacturability, and return feedback within 24 hours.Click to get a quote for your titanium alloy parts.

FAQs

Why is titanium difficult to machine?

Titanium traps heat at the cutting edge and resists shear, which increases tool wear and makes the cut less stable than aluminum or stainless steel.

Which titanium grades are best for CNC machining?

Grade 2 machines easier, while Grade 5 (Ti-6Al-4V) provides much higher strength and is widely used in aerospace and medical components.

What tolerances can be achieved on titanium CNC parts?

±0.02 mm is typical under stable conditions. Tighter tolerances are possible with controlled heat and rigid tooling.

Why does machining titanium cost more?

Cycle times are longer, tools wear faster, and setups must be extremely rigid. These factors increase machining time and tooling cost.

How can engineers reduce the cost of machining titanium?

Use larger corner radii, avoid deep pockets, keep wall thickness consistent, and choose Grade 2 when high strength is not required.