Low-volume CNC machining typically refers to short production runs made from real engineering materials, often ranging from a few pieces to a few hundred parts. The exact quantity is rarely fixed. What defines “low-volume” is the context: the design is still evolving, functional validation is ongoing, or the program is not yet stable enough to justify tooling. When parts must perform, fit correctly, and reflect real material behavior—but future changes are still likely—low-volume CNC machining becomes the practical manufacturing choice.

Most engineering teams recognize this stage immediately. CAD may look finished, but the first physical build exposes small but meaningful issues: a fastener clearance that feels too tight, a mating surface that needs refinement, or a tolerance that proves unrealistic once parts are assembled. Low-volume CNC machining fits this moment because revisions remain manageable, and learning happens without locking the project into premature tooling decisions.

What “Low-Volume” Really Means in CNC Projects

From an engineering perspective, low-volume is less about quantity and more about program maturity. A run of 30 parts can be considered low-volume if geometry is still changing, while a run of 300 parts may also qualify if it serves as a bridge before a long-term production process is selected.

In practice, low-volume CNC machining often appears in three common scenarios. The first is functional prototyping, where a small batch is produced to evaluate fit, strength, and real-world performance. The second is pilot production, where dozens or hundreds of parts are required for early customer builds, regulatory testing, or limited releases. The third is short-run production for programs with uncertain demand, where committing to tooling would introduce unnecessary financial risk.

If this sounds familiar, it is because many hardware projects spend more time in this phase than initially expected. Even designs labeled as “final” frequently change once real parts interact with real assemblies.

Why Engineers Choose Low-Volume CNC for Functional Parts

Functional parts impose a different level of scrutiny than visual or conceptual models. Components that carry load, seal against fluids, align with purchased hardware, or integrate into larger assemblies must behave predictably under real conditions. In these cases, low-volume CNC machining is selected not because it is the cheapest option, but because it preserves engineering flexibility.

One common reason is ongoing design evolution. When revisions are likely, CNC machining allows geometry changes to be implemented directly in CAM without reworking tools. Programming and setup effort still exist, but they remain proportional to the change rather than exponential.

Another reason is tolerance validation. Many drawings specify conservative tolerances early in development, only to discover later that a few features control the entire assembly. Low-volume CNC machining makes it possible to identify which dimensions truly matter, tighten them where necessary, and relax the rest. Teams that have worked through tolerance stack-up issues know how valuable this clarity can be.

Material authenticity also plays a major role. Functional validation performed on non-production materials often produces misleading results. CNC machining allows engineers to test parts in aluminum, steel, stainless, or high-performance plastics such as PEEK, ensuring that strength, wear, thermal behavior, and chemical resistance are evaluated accurately.

Prototyping With CNC: When Appearance Is Not Enough

Many prototyping efforts begin with appearance models, and that approach works until functional testing becomes critical. Once parts must support loads, maintain alignment, seal, or withstand environmental exposure, surface-level similarity is no longer sufficient.

Low-volume CNC machining supports functional prototyping by delivering accurate geometry, realistic surface contact, and consistent material behavior. When issues such as galling, cracking at sharp transitions, thread pull-out, or thermal distortion appear, they tend to surface quickly in CNC-machined prototypes. Identifying these problems early often prevents far more expensive redesigns later.

CNC prototypes also provide valuable manufacturing feedback. Tool access challenges, burr-prone features, and unnecessarily tight tolerances become visible once parts are machined. This feedback helps engineers refine designs not only for performance, but also for manufacturability.

Cost Structure in Low-Volume CNC Machining

Cost in low-volume CNC machining is primarily driven by engineering effort rather than scale. Understanding where that cost comes from helps teams make realistic decisions during early builds.

Programming and setup represent the first major contributor. Toolpath strategy, workholding design, datum selection, and inspection planning all require upfront effort. In low-volume CNC machining projects, these costs are not spread across thousands of parts, which explains why part complexity often matters more than part size.

Material utilization is another factor. Short runs may rely on standard stock sizes that are not optimized for yield, particularly for thick sections or high-value materials. Scrap and offcut losses become part of the true cost picture.

Secondary operations frequently dominate total cost. Deburring, surface finishing, thread inserts, heat treatment, coating, or cosmetic requirements can exceed cutting time. Inspection effort also increases when tight tolerances are applied broadly rather than selectively. Low-volume CNC machining is most efficient when tolerances and finishes are specified based on function, not caution.

Tolerance Expectations for Low-Volume CNC Parts

For most functional components, low-volume CNC machining can reliably achieve precise and repeatable dimensions when designs are machining-friendly and materials are stable. Challenges arise when tolerance requirements are applied uniformly without considering functional necessity.

Extremely tight tolerances drive cost through slower machining strategies, increased tool wear management, more intensive inspection, and sometimes additional process controls to manage heat and distortion. These measures are justified when function demands them, but they become wasteful when applied indiscriminately.

A focused tolerance strategy—tight where function requires, relaxed elsewhere—allows low-volume CNC machining to deliver both performance and cost efficiency. Teams that adopt this approach typically see faster iteration and more predictable outcomes.

When Low-Volume CNC Machining Stops Making Sense

There is a clear point where low-volume CNC machining is no longer the most practical solution. This point is usually reached when geometry is frozen, materials are finalized, and demand becomes predictable.

At that stage, unit cost begins to outweigh flexibility. Processes such as injection molding become more attractive as tooling costs can be amortized over stable volumes, and cycle efficiency improves dramatically. Reaching this transition is not a failure of CNC machining, but a sign that the program has matured.

When part geometry stabilizes and repeat volumes increase, the discussion often shifts toward tooling-based processes. At that point, low-volume CNC machining versus injection molding becomes a practical comparison rather than a theoretical one.

Low-volume CNC machining is intended to support learning and adaptation. Once learning slows and repetition dominates, scaling processes deserve attention.

How Engineers Decide Between Low-Volume CNC and Other Processes

In practice, the decision often comes down to identifying the primary risk. When design risk remains high, low-volume CNC machining protects the program by keeping changes affordable. When cost risk becomes the dominant concern and designs remain unchanged, production-oriented processes take priority.

Many teams follow a phased strategy: functional CNC prototypes, limited pilot runs, and eventual transition to molding or other high-volume methods. If a project currently sits between CNC machining and injection molding, that usually indicates it is nearing a decision boundary rather than a mistake.

Choose JeekRapid CNC Machining Services

Low-volume CNC machining is not simply a prototyping step, nor is it a substitute for high-volume production. It is a deliberate manufacturing strategy used when parts must be functional, timelines are tight, and design certainty has not yet been achieved.

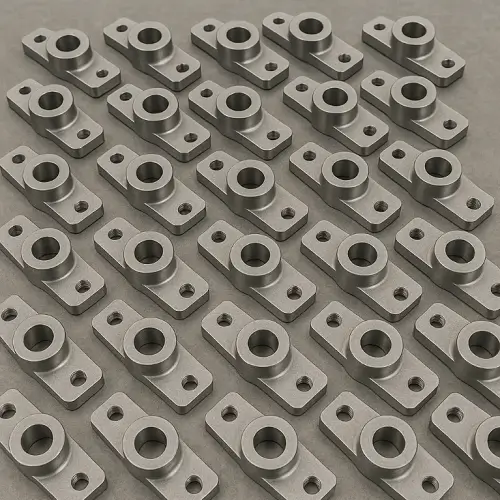

At JeekRapid, low-volume CNC machining is typically applied during this transitional phase, where parts need to be real, repeatable, and representative of final performance, but design refinement is still expected. Short CNC runs are often used to validate tolerances, material behavior, and assembly fit before any commitment is made to tooling or large-scale production.

Whether a project remains in low-volume CNC machining or progresses toward injection molding depends on what those early parts reveal. In many cases, a controlled CNC build provides the clarity needed to make that decision with confidence rather than assumption.If you currently have parts that need to be manufactured and need Jeekrapid to help you with small-batch production, click here to get a quote for small-batch parts!

FAQs

What is considered low-volume CNC machining?

In most engineering projects, low-volume CNC machining refers to short production runs typically ranging from a few parts to a few hundred pieces. The defining factor is not the exact quantity, but whether the design is still evolving and whether tooling would introduce unnecessary risk at the current stage.

Is low-volume CNC machining only for prototypes?

No. While it is widely used for functional prototypes, low-volume CNC machining is also common for pilot production, early customer builds, and short-run manufacturing where demand is uncertain or design changes are still expected.

How does low-volume CNC machining compare to injection molding?

Low-volume CNC machining offers greater flexibility and faster design changes, while injection molding becomes more cost-effective once part geometry is stable and production volumes are predictable. CNC is often used first to validate function and tolerances before molding is justified.

What materials are typically used in low-volume CNC machining?

Low-volume CNC machining commonly uses production-grade materials such as aluminum alloys, carbon steel, stainless steel, engineering plastics, and high-performance materials like PEEK. Using real materials allows functional testing to reflect actual service conditions.

When should a project move from low-volume CNC machining to molding?

The transition usually makes sense when part geometry is finalized, tolerances are proven, material selection is fixed, and repeat volumes are high enough to amortize tooling costs. At that point, unit cost and cycle efficiency become more important than flexibility.

Does low-volume CNC machining support tight tolerances?

Yes, but tolerances should be applied selectively. Low-volume CNC machining can achieve precise dimensions, but overly tight tolerances across non-critical features can increase cost without improving part function.