CNC turning machines continue to play a foundational role in modern machining operations. While multi-axis milling and hybrid platforms receive much of the attention, turning remains one of the most efficient and stable processes for producing rotational parts in real production environments.

In practical manufacturing, the value of a CNC turning machine is not defined by how advanced the control system appears on paper, but by how reliably it maintains alignment, concentricity, and surface consistency once the process is running. Understanding where turning works best—and where it does not—helps engineers avoid unnecessary complexity early in the machining plan.

What Are CNC Turning Machines?

CNC turning machines are machine tools that remove material by rotating the workpiece against stationary cutting tools. Material removal is primarily aligned with the rotational axis, making turning particularly effective for cylindrical, conical, and axisymmetric geometries.

In everyday shop-floor discussions, CNC turning machines are often referred to as CNC lathes. While terminology varies, the operating principle remains the same: the part rotates, and cutting tools follow controlled paths to generate features relative to a single centerline.

This approach differs fundamentally from milling, where the cutting tool rotates and the workpiece remains fixed in position.

How CNC Turning Machines Work

A CNC turning machine operates by clamping the workpiece in a chuck or collet and rotating it at a programmed speed. Cutting tools mounted on a turret move along defined axes to remove material according to the machining program.

Most turning machines rely on two primary axes. The Z-axis runs parallel to the spindle centerline and controls longitudinal motion, while the X-axis controls radial depth of cut. More advanced machines may include additional axes that allow spindle indexing, off-axis drilling, or limited milling operations.

Because the workpiece rotates continuously during cutting, turning naturally preserves the relationship between features along the spindle axis. This characteristic is one of the reasons turning is widely used for parts where alignment between multiple diameters and bores is critical.

Main Components of CNC Turning Machines

Although configurations vary, CNC turning machines share several core structural elements that define how they behave during machining.

The spindle and chuck hold and rotate the workpiece. Spindle rigidity, balance, and bearing condition directly influence surface finish and dimensional stability. For longer or slender parts, a tailstock or steady rest is often required to control deflection during cutting.

The tool turret carries multiple cutting tools and indexes them into position as required. Turret repeatability affects both cycle time and dimensional consistency, especially in production environments where the same toolpaths are repeated over long runs.

The axis system controls tool motion. Basic machines operate on X and Z axes, while more advanced turning centers may include Y-axis motion, C-axis control, sub-spindles, or live tooling to support secondary features.

Together, these elements form a system optimized for stable rotational machining rather than complex surface generation.

Types of CNC Turning Machines

CNC turning machines are commonly categorized by spindle orientation and machine layout. In most shops, the first practical distinction is horizontal versus vertical turning. From there, machines can be further defined by axis configuration and whether milling capability is integrated.

Horizontal CNC Turning Machines (Horizontal CNC Lathes)

Horizontal turning machines are the most common configuration in general machining. The spindle is parallel to the floor, and the workpiece is held horizontally in a chuck or collet.

This layout is widely used for shafts, sleeves, spacers, and general rotational parts because setup is straightforward, tool access is predictable, and chip evacuation is stable for most standard turning operations. Horizontal lathes are also commonly paired with bar feeders for production work, especially when parts are made from round stock.

Vertical CNC Turning Machines (Vertical Turning Lathes)

Vertical turning machines hold the workpiece on a rotating table, with the spindle oriented vertically. The part is supported by gravity, which makes this configuration well suited for large-diameter or heavy workpieces that would be difficult to support horizontally.

Vertical turning is often used for large rings, flanges, valve bodies, and similar components where workholding stability and safe handling are key considerations. In many cases, the primary reason for choosing a vertical turning machine is not machining capability, but part support and process stability.

2-Axis CNC Turning Machines (X/Z)

Once spindle orientation is defined, axis configuration becomes the next practical distinction. Two-axis turning machines use X and Z motion to machine external diameters, internal bores, faces, and grooves.

This configuration is common for parts where features remain coaxial and off-axis machining is not required. It is also one of the easiest turning setups to stabilize in production because toolpaths and workholding remain simple.

Multi-Axis CNC Turning Centers (Y-Axis, C-Axis, Live Tooling)

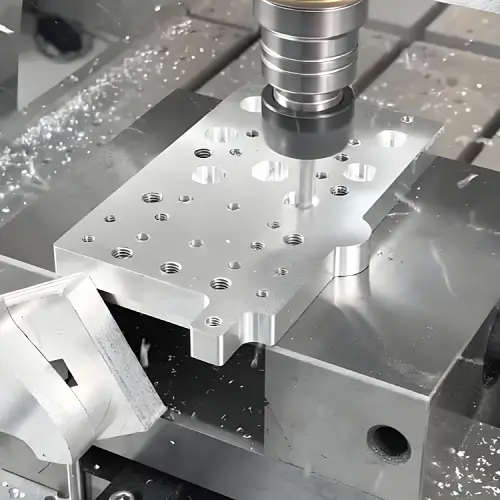

Multi-axis turning centers extend basic turning capability by adding features such as Y-axis motion, C-axis spindle control, and live tooling. These machines can perform drilling, slotting, and limited milling operations without removing the part from the machine.

They are typically selected when parts require features distributed around the circumference—such as cross-holes, flats, keyways, or bolt patterns—where secondary milling setups would increase alignment risk or handling time.

Mill-Turn Machines

Mill-turn machines combine turning and milling functions into a single platform. They are used when parts require both rotational features and prismatic geometry, particularly when minimizing setups is more important than maximizing pure turning efficiency.

In production environments, mill-turn machines are often selected for complex housings, precision connectors, and parts that require tight feature-to-feature alignment across multiple orientations.

What CNC Turning Machines Are Used For

CNC turning machines are primarily used for parts where rotational symmetry defines both geometry and function. In these cases, maintaining concentricity, roundness, and axial alignment is more critical than producing complex freeform surfaces.

In most production environments, turning is selected not because it is advanced, but because it keeps critical features aligned with minimal process risk.

Shaft-Type and Rotational Components

Turning is widely used to manufacture shafts, pins, bushings, spacers, and sleeves. These parts often require tight control of diameter, straightness, and coaxial alignment across multiple features.

Because all critical dimensions are referenced to a single rotational axis, turning maintains these relationships naturally without relying on repeated re-fixturing.

Cylindrical Housings and Structural Parts

Many industrial housings and cylindrical structural components begin with turning operations. Stepped outer diameters, internal cavities, precision bores, and sealing grooves can often be produced in a single setup.

This approach is particularly useful when internal and external features must remain aligned after assembly or during service.

Precision Bores and Internal Features

Turning machines are commonly used for parts that require accurate internal diameters, controlled wall thickness, and consistent surface finish inside bores. Cutting forces remain balanced around the rotating axis, which helps maintain dimensional predictability during internal machining.

Typical applications include bearing seats, hydraulic components, and press-fit interfaces where small deviations can affect performance or service life.

Production Parts Requiring Repeatability

In production environments, CNC turning machines are often selected when repeatability and process stability matter more than geometric complexity. Once a turning process is stabilized, it can deliver consistent results across large batches with minimal variation.

This makes turning a preferred process for automotive components, industrial hardware, and general mechanical parts produced at scale.

Advantages and Limitations of CNC Turning Machines

CNC turning machines offer advantages that are rooted in mechanical structure rather than software complexity. Most of their strengths come from how the workpiece is supported, rotated, and referenced during machining.

Understanding these structural strengths—and their corresponding limits—helps prevent turning from being applied in situations where milling or hybrid processes would provide better results.

Structural Advantages of CNC Turning Machines

One of the primary advantages of CNC turning machines is the geometric stability created by rotating the workpiece around a fixed spindle axis. When critical features share a common centerline, turning preserves alignment without relying on complex fixturing strategies.

Turning also distributes cutting forces evenly around the rotating axis. This balanced loading improves dimensional predictability, particularly for long or slender components that might deflect under off-axis cutting forces.

Once a turning process is stabilized, it tends to deliver high repeatability. Toolpaths remain simple, setups are consistent, and deviations are easier to detect compared to multi-directional machining operations.

Process Efficiency and Control

Turning machines are well suited for efficient material removal on cylindrical stock. Continuous cutting paths lead to predictable chip formation and heat generation, reducing variability during machining.

Tool access is straightforward, with most features referenced directly from the spindle axis. This simplicity often reduces setup time and supports stable production cycles, particularly in higher-volume manufacturing.

Limitations Inherent to Turning Machines

CNC turning machines are constrained by their reliance on rotational symmetry. Features that fall outside the primary spindle axis—such as angled surfaces, complex pockets, or non-coaxial patterns—are not naturally suited to turning.

When such features are required, additional setups, live tooling, or secondary milling operations become necessary. Each added operation increases process complexity and introduces potential alignment risk.

Turning is also not well suited for large planar surfaces or freeform geometry. Attempting to force these features into a turning-based workflow often results in inefficient toolpaths or compromised surface quality.

Choosing Turning for the Right Reasons

In real machining work, turning is usually chosen when the most critical features of a part can be referenced to a single centerline. This often becomes clear during drawing review, when multiple diameters, shoulders, and bores must remain coaxial after machining and assembly.

A common example is a stepped shaft or sleeve where dimensional relationships along the axis matter more than individual surface details. In these cases, turning keeps those relationships intact without relying on multiple fixtures or reorientation steps.

Problems tend to appear when turning is selected for parts that only appear rotational at first glance. If key features require access from multiple directions, or if flat surfaces and angled profiles dominate the design, forcing everything into a turning-first approach usually leads to secondary setups, added milling operations, and unnecessary complexity. In such cases, turning works best as one stage in the process rather than the primary solution.

CNC Turning Machines vs Milling Machines

The difference between turning and milling becomes clear when looking at how each process establishes its reference. Turning locks critical geometry to the spindle axis, while milling builds geometry relative to a workholding datum or fixture surface.

Turning is most effective when roundness, concentricity, and axial alignment define part performance. Milling excels when flatness, pocket geometry, angular features, or freeform surfaces dominate the design.

In many real-world parts, neither process works alone. A housing may be turned first to establish concentric bores and outer diameters, then milled to add mounting faces or ports. Treating turning and milling as competing processes often leads to poor decisions, while treating them as complementary steps usually results in a cleaner machining sequence.

How CNC Turning Machines Fit Into Modern Machining

Despite the availability of advanced multi-axis platforms, CNC turning machines continue to handle a large share of precision work on the shop floor. This is not because turning machines are more capable in a general sense, but because they solve a specific class of geometric problems with very little process risk.

For rotational parts produced in volume, turning offers predictable tool engagement, stable chip formation, and consistent dimensional control once the process is established. These characteristics make variation easier to detect and control.

In modern machining workflows, turning machines are most effective when they are used deliberately for what they do best rather than as flexible machines expected to cover every feature. When part geometry aligns with that role, turning remains one of the most reliable and repeatable machining methods available.

Conclusion

CNC turning machines remain one of the most reliable tools for producing rotational components in modern manufacturing. Their strength lies not in flexibility, but in stability—maintaining alignment, repeatability, and predictable results when part geometry aligns with the process.

For projects where turning is a potential fit, early review of part geometry and machining strategy can prevent unnecessary setups and downstream issues. If drawings are available, evaluating turning feasibility at this stage helps ensure the process is matched to the part, not forced onto it.

If you would like feedback on whether CNC turning is the right approach for a specific part, drawings can be reviewed to assess machining strategy, setup risk, and production feasibility before moving forward with a quotation.

FAQs

What types of parts are best suited for CNC turning machines?

CNC turning machines are best suited for parts with rotational symmetry, such as shafts, bushings, sleeves, rings, and cylindrical housings. Parts that require tight concentricity, roundness, and axial alignment benefit the most from turning.

Can CNC turning machines handle tight tolerances?

Yes. CNC turning machines can hold tight tolerances on diameters and bores when the process is properly controlled. Because all critical features are referenced to a single spindle axis, dimensional relationships tend to remain stable across production runs.

When should milling be used instead of turning?

Milling is more suitable when parts require flat surfaces, complex pockets, angled features, or geometry that cannot be referenced to a single rotational axis. In many cases, turning and milling are used together rather than as alternatives.

Are multi-axis turning centers always better than 2-axis machines?

Not necessarily. Multi-axis turning centers offer greater flexibility, but they also introduce more complexity. For parts with purely coaxial features, a well-set-up 2-axis turning machine is often more stable and cost-effective.